Gravity – A discourse on diatonicism

Please don’t let yourself be intimidated by the fancy title. My self-imposed job is to break those concepts down, so that anybody can understand them and I’ll try my best to achieve that. Just imagine yourself using those fancy terms once you’ve learned that…! Or really any term that fits the idea.

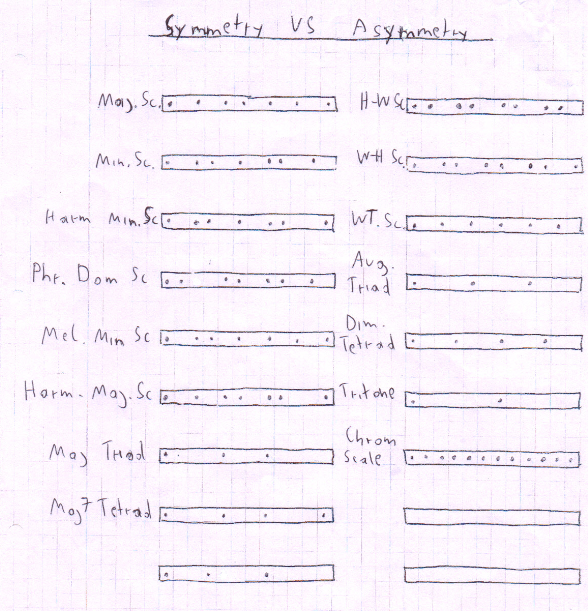

What do I mean by gravity? In the articles Introduction to Harmony Part II and III, I explain functional harmony. This pull that can be felt, from the goal chord (the dominant), back to the home chord (the tonic), represents the major scales gravitational pull. What we have to take a look at now is: how is that pull generated? The answer is Asymmetry. Any structure that is asymetric has gravity. Now, you might wan’t to ask: “Paul, what the hell is this Asymmetry bullshit, you keep going on about you postmodernist piece of scum!?” And rightfully so. Let me demonstrate it with a few pretty pictures. I drew them myself.

Maybe you can tell from those pictures, what the term “symmetry” means in a musical context. A symmetrical structure’s has at least one inversion, which is identical with the original structure (in root position). In other words: There are notes within the chord or scale, that yield the same chord or scale if you start building it from that note. Now, these symmetrical structures are very useful and fairly easy to play. Read this article to learn about how they can be applied. But for the sake of this article it is important to know what they are not useful for, namely the implication of an unambiguous tonal center and the providing of a gravitational pull towards it.

Meanwhile, in your brain

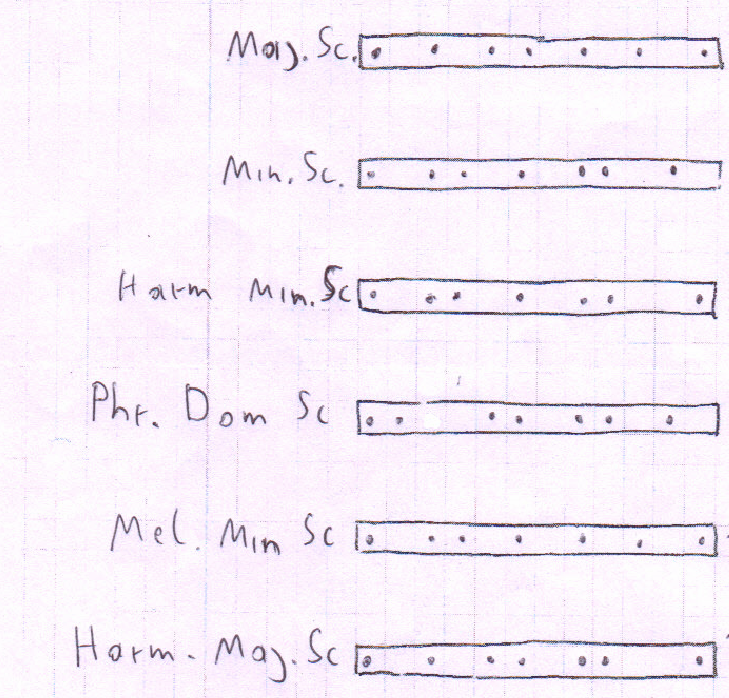

On the upper left side you can see 4 of the mother scales. They are all diatonic, as they can be obtained by stacking thirds on top of the root. The Minor and the Phrygian Dominant Scale don’t belong in there, as they can be derived from the others.

All of them possess an unambiguous tonal center. Whenever you play around with those sets of notes and imply different chords either harmonically or melodically (as opposed to purely modal playing), it will only sound totally resolved if you end it on the root. Now there is one problem. These structures are pretty similar to each other. They all contain some identical chords on the triad level, many even on the tetrad level. So, to which of those mother scale do these identical chords point us? The answer is: to the simplest one possible. As in, the one that is simpler mathematically speaking. This goes all the way down the rabbit hole to tendency tone analysis. Harmonic Major is more complex than Natural Major. Just look at the chords that can be derived from it. If those arent implied, why would we think of them? Harmonic Major is only in use if one of the Harmonic Major-specific chords is being played. It is also important to understand that a switch from one of those scales to another is something, that happens very dynamically. They are not mutually exclusive during the recital of a particular song. In fact, they could change all the time and one can write compelling music in which that happens. Check out the article on Modal Interchange to learn more about how this works.

So, the major scale is the go to scale for our brain. We tend to relate everything we hear to the major scale, unless something else is explicitly implied. Like a minor third, for instance. If the minor third is implied we will associate everything to the sixth mode of the Natural Major scale – the Natural Minor Scale, and whenever needed to the Harmonic Minor Scale, which provides unambiguous gravity towards a key center in a Minor context, unlike the Natural Minor Scale. Sometimes one might also hear some ambiguous notes and just be in a “minor mood” and have the brain interpret them in a minor context. For instance, let’s say we hear some car alarm going of in the distance, and it’s some note followed by it’s fifth. Our brain could go

“Daaah Daaah, da da da daaah dah…”

from “Star Wars Theme

or

“Flintstones, meet the Flintstones…”.

from “Flintstones Theme”

That’s a perect fifth in a major context. If we’re in a minor mood we might of course also hear

“Raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens…”

From “My Favourite Things

or

“What shall we do with the drunken sailor…”

from the shanty “Drunken Sailor”

In this case our brain itself implied the minorness.

But what about chords?

The same is true for chords. It’s even easier to understand this with chords, as there are fewer variables (fewer notes) in play. Our brain will always try to relate all the notes to a key center. It does this depending on several factors:

- Ambiguity of the chord: What structure is the chord? Our brain easily deciphers diatonic triads and tetrads, as the individual notes can be put into relation with each other by stacking of thirds. What about non-diatonic triads or tetrads? These are a lot harder. For instance, what if you have the following combination of notes: AEB? This structure can not be obtained by a stacking of thirds. How our brain interprets them is depending on:

- Existing context: Is the chord played as part of a chord progression? If it’s played in an A Major context, we will hear it as an Asus9 chord. In an E Major context however, we might hear an Esus4. If there is no particular context our perception depends on:

- Inversion of the chord: How the chord is voiced has quite a lot of impact on how we perceive it, especially if there is no existing context. Play the AEB structure with an A in Bass and we will more likely than not hear it resolve to A Major in our head. Guess what we’ll hear if E is in the bass?

- Cultural association: One more factor that plays a role. Certain chords are engrained into our thinking in a specific way. We have to thank people like JS. Bach for this, as they laid the foundation for much of todays musical practice. This is particularly true for specific voicings. Adam Neely did a great video dealing a bit with this subject.

I hope this was useful to you and could bring some clarity regarding how we perceive sound. After all one of the things I’m trying to do here is to bring unambiguity to musical ambiguity. An to torture people with big fancy words. Stay tuned for more of those!

Do you have a spam problem on this website; I also am a blogger, and I was wondering your situation; many of us have developed some nice methods and we are looking to swap solutions with others, be sure to shoot me an email if interested.