An Introduction to voicings

Voicings are something, many musicians don’t spend enough time thinking about. For each chord, there are multiple ways of playing it and choosing the one that fits the song best can add a lot of depth to it. Some thought that has been put into the voicing of chords, is what often distinguishes a hit song from a murky cover version. Voicings are quite important when you hit a certain level of musicianship, there is no way around it. The rules of what sounds good and what not are fairly simple, although there are some differences of what can be played depending on the instrument. In the first article in this series I’ll present all voicing possibilities for triads I found on the guitar. Maybe there are some I didnt find, I’d be happy to have them presented in the comment section! Although there are vastly more possibilities to voice chords on the piano, this article will also be a good place to start for any pianist that wants to learn about chord voicings.

Before I start I want to briefly explain what we’ll look at. I can think of seven things to consider:

- The harmonic density (triad, tetrad, quintad…)

- The voicing type

- It’s spacing

- It’s consonance

- It’s inversions

- It’s applicability on different instruments

- How to practice it

Triad voicings

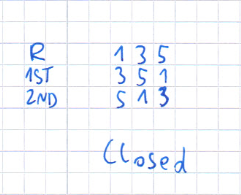

First of all, let’s start with all possible ways a triad can be voiced. The simplest kind is called the closed position voicing. What this means, is that it’s chord degrees are directly stacked on top of each other. So the root, then the third and lastly the 5th. This gives us the tightest voicing possible. Since the notes are all a diatonic third apart, there will be no clashes between notes and it will sound very orderly and consonant.

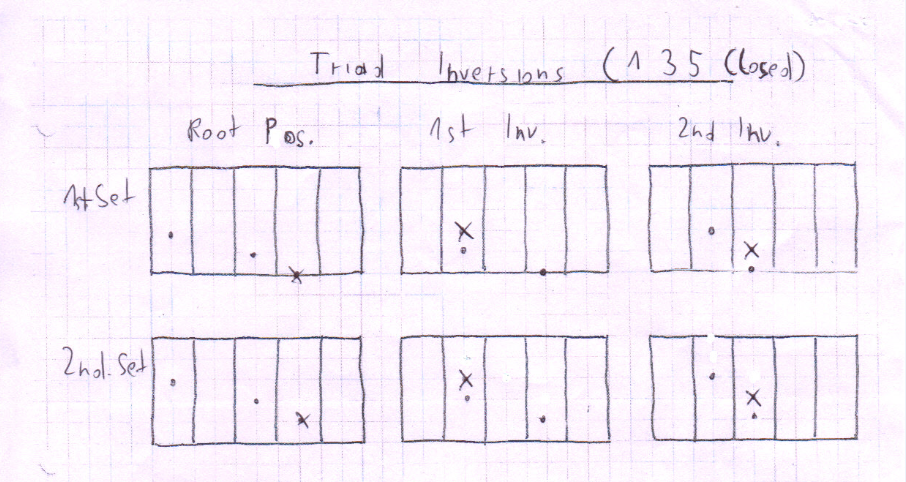

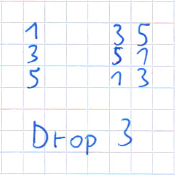

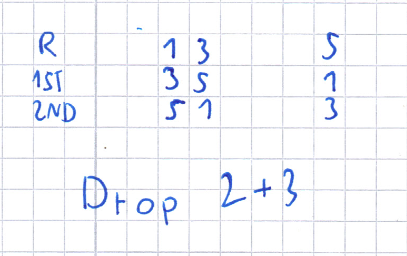

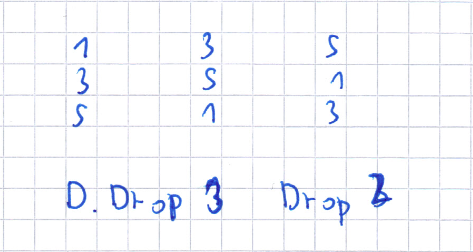

These are all the inversions of a closed position triad (Root Position, 1st Inversion, 2nd Inversion). The way you get those is fairly simple. It’s the same process for any voicing. You just go one chord degree further from each note of the previous inversion (If you’re on the highest chord degree, you go to the root), look at the pictogramm for reference. Since you can easily play this structure on each set of three adjacent strings, you’ll have 4 Sets to learn, which gives you a total of 12 possibilities to play a closed triad. Then, of course, there are 4 possible triads, which yields a total of 48 shapes to remember (actually a few less due to the symmetrical nature of the augmented triad, but we’ll get to that). This is where we have to get selective.

Here are the first few of the major triad, so you have an idea how it would look. Do not attempt learning all of this for no good reason. Instead, look for a way to apply this musically. Once you have an application, learning will be much easier, as you’ll see the structure in a musical context and will train it automatically, whenever you use it in your playing. The essential triads are, of course, the major and minor ones. The augmented triad is super easy (due to it’s symmetrical nature) and can be a lot of fun, if you know when and where to use it. The diminished one has it’s uses as well, for sure, but is quite hard, especially if you’re new to this topic and prone to confuse it with other shapes. Here is how all of them are constructed.

All of this is absolutely applicable on guitar, as well as piano and can help you give character to a chord progression and ultimately, also in finding your own sound. The most basic way to train those structures is to take ’em through the major scale. I would also recommend you to download and print out the blank sheet for chord shapes and find all the minor and major triad shapes on your own, which will help you in memorizing them. Another really useful approach I’d recommend is training them by using the three lines visualisation method. It will help you to integrate closed position triads in your improvisation.

Let’s take a look at some other triad voicings:

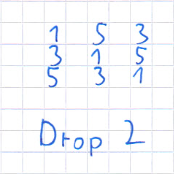

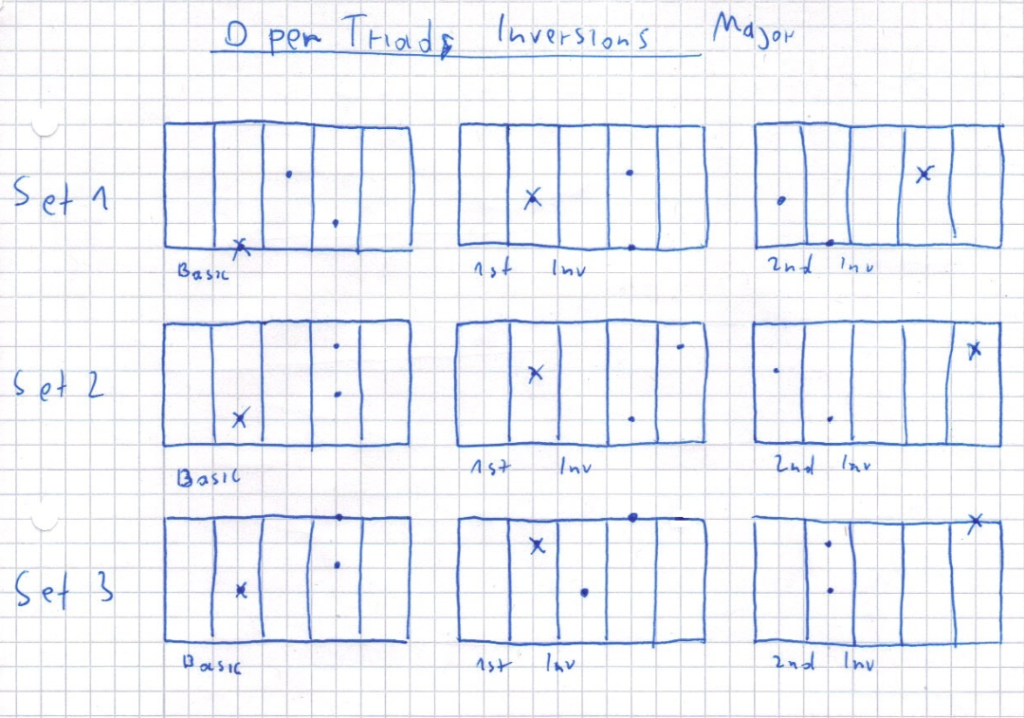

This is what they call an open triad. What happened in relation to the closed triad is that the 3rd moved up an octave, while the fifth stayed where it was. On the guitar you need a span of 4 strings to play that structure, which yields only 3 sets to learn. So, times the 3 inversions (including root position), this gives us 9 possibilities for each triad type.

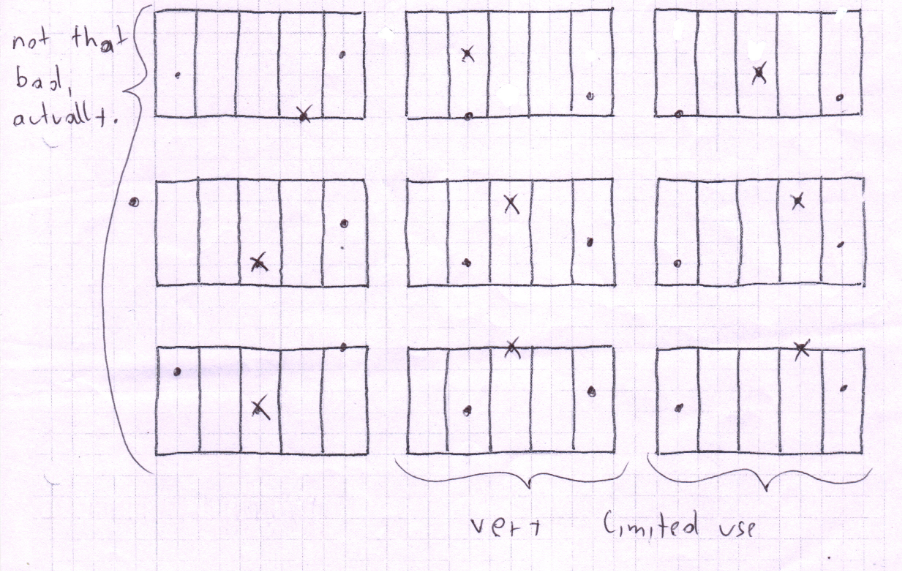

So, here are all of the 9 possibilities. But. Notice something? There are actually more ways to finger the same voicing within our 4 string paradigm. This is due to the string we skipped. But maybe some are crap… Let’s find out which.

All of the upper 9 voicings consonant and most also really useful. Personally I like the alternative shape of the root position one. It’s not impossible and it allows you to play chromatic line clichés from the fifth pretty easiliy, for which I usually use this specific shape. The other two are kinda tricky. So far, I haven’t found any use for them. But maybe you have. I’d be delighted to get to know about that in the comment section! Anyways, whichever you prefer, find the individual inversions by using the method described earlier and take them up and down the major scale.

Our next voicing is the following:

What happened there is that we also moved the fifth up an octave. Now, this voicing is pretty. It is actually contained in any E- or A-shaped based bar chord we play. This is the perfect example that less is more sometimes. I love this voicing and all its inversions. The way the bass note interacts with the high ones gives me a shiver, the good kind. Whenever something gives you this reaction in music, MAKE IT YOURS!

Since it’s quite spread apart, only two sets are available, which gives you 6 shapes total. There are a couple of alternative shapes but they don’t make that much sense, at least for human fingers. These are alo quite applicable because they are quite easy to finger and give a very specific sound. You know the drill. Major scale. Go go go!

Here is another voicing option you might want to try out:

Our final voicing will be that thing:

Now we took the third another octave up, taking the guitar pretty much to it’s harmonic limit when it come to moveable shapes. Granted, those are not the most practical ones, especially the last one, but it’s good to have seen the limit of your instrument once. The root position one is only playable by baring the root and the fifth and then it’s quite a stretch to the third. The first inversion is also “kinda playable”. Forget about the second inversion.

I hope this was useful to you. The goal of your practice should be to recognize those shapes in larger chord and scale patterns (this will happen automatically over time) and be able to voice chords dynamically on different sets of strings. Just imagine any chord breaking during improvisation! Now you’re totally prepared. Stay tuned for the next article, which will go further into the land of seventh chord voicings and explain the voicing nominclature a bit.

I am sure this post has touched all the internet users, its really really nice

piece of writing on building up new web site.

buying cialis online tadalafil 20mg mylan cialis avis cialisfr2022

tadalafil research stop cialis dose generic cialis names

tadalafil ohne rezept female cialis dose cialis mg dosage

tadalafil maxigra doz viagra and cialis cialis work

viagra medication viagra nebenwirkungen wikipedia viagra prescription canada

viagra magnus sildenafil viagra dosage sizes sildenafil citrate msds

cialis quantity limit cialis daily pill cialis medication use

tadalafil mexico price tadalafil 40mg canada tadalafil bulk

viagra coupon costco pde4 inhibitor viagra viagra capsule

tadalafil 5mg instructions indian tadalafil tadalafil opinie forum

viagra prostate cancer sildenafil citrate msds viagra jet 100

prevent viagra headaches viagra tablets dosage viagra expiration patent

cialis buy cialis drug company bph medicaid cialis

5mg tadalafil cialis prices costco cialis before gym

viagra prices us sildenafil dosering verhogen viagra type pills

cialis drugstore heallthllines cialis pill images tadalafil leberwerte

who makes viagra sildenafil blue pill sildenafil form

cialis dont work cialis generic name tadalafil legal

viagra lowest cost viagra sildenafil dosage viagra checklist pdf

levitra overdose levitra maximum dosage levitra 20mg bnf

viagra savings coupons sildenafil price mexico sildenafil citrate walmart

vardenafil vs sildenafil levitra funcion vardenafil 20mg australia

sildenafil 100mg kaufen viamedic viagra coupon viagra telemedicine

viagra connect superdrug viagra tabletten kosten viagra price mexico

womens viagra effects viagra taiwan price viagra mac opinie

levitra lasting effects levitra takes effect vardenafil best price

viagra billboard sildenafil mylan 50mg sildenafil dosage chart

sildenafil tableta 50mg viagra sildenafil 100mg sildenafil citrate webmd

levitra originale prezzo levitra fiyat levitra commercial

viagra coffee sildenafil chest pain teva sildenafil coupon

sildenafil precio guatemala sildenafil hond dosering effects viagra men

levitra contents levitra einsatz pastillas levitra precios

viagra tx viagra patent history sildenafil boots online

sildenafil goo sildenafil mark cuban g4 sildenafil tabletas

once daily levitra levitra uk pharmacy levitra pill appearance

sildenafil for women sildenafil nitrates interaction viagra thailand price

viagra 50mg review viagra coupon card viagra men

daily tadalafil nhs cialis otc rx cialis usa kaufen

levitra generika uk vardenafil precio levitra remedio preco

sildenafil mylan pfizer viagra generic viagra connect canada

sildenafil vardenafil good viagra alternative viagra heart failure

tadalafil research capsules cialis tabletki tadalafil sandoz prix

viagra singapore sildenafil citrate vigora100 viagra information

sildenafil precio colombia sildenafil tablets viagra sildenafil tableta

cialis vision changes women using cialis cialis and fatigue

sildenafil manforce 100mg viagra visual changes viagra connect list

levitra avis doctissimo levitra medication uses vardenafil in bangladesh

viagra coupons kroger sildenafil price canada sildenafil mylan 50mg

viagra pillow viagra pricing canada roman viagra

no prescription cialis cialis precio mexico cialis principio ativo

viagra boys setlist viagra austin tx viagra toxicity